The Stamp Act of 1765

Patrick Henry, a newly elected burgess from Louisa County, led the protest against the Stamp Act in the House of Burgesses. Working with fellow burgesses John Fleming and George Johnston, Henry challenged the constitutionality of the Stamp Act. He introduced five resolutions in the House of Burgesses on 30 May 1765. The first four resolutions stated that the colonists

had all the rights and privileges of Englishmen,

that only the people or their elected representatives could levy a tax on them,

and that this right was part of the constitution, recognized by the kings and people of Britain.

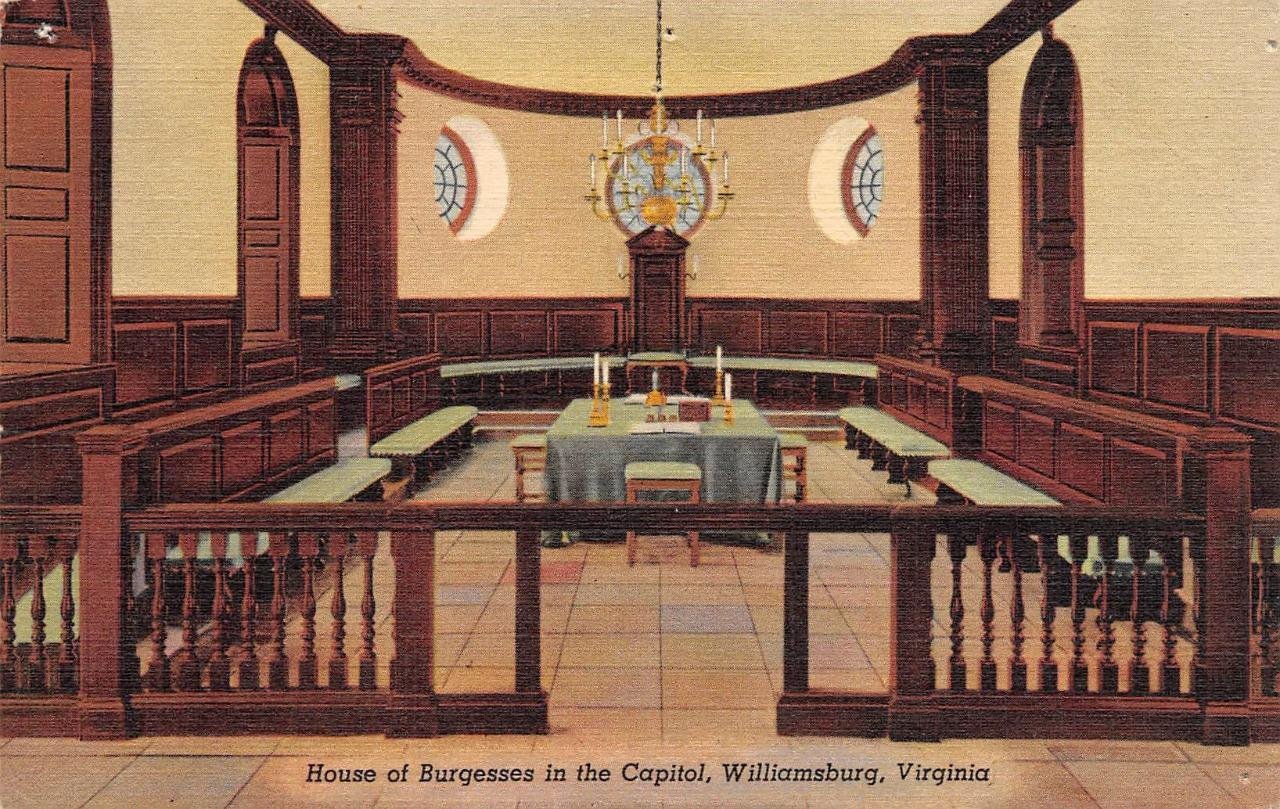

House of Burgesses, Williamsburg, VA facing Francis Street [photo by Rebecca Raupach]

The fifth resolution radically declared that only the House of Burgesses had the right to tax the inhabitants of the colony.

In support of his resolutions, Henry made a dramatic speech, described by an eyewitness as “one of the members stood up and said he had read that in former times Tarquin and Julius had their Brutus, Charles had his Cromwell, and he did not doubt but some good American would stand up in favour of his Country.” Another first hand account, although written many years after the event, recalled that Henry declared “Tarquin and Caesar had each his Brutus, Charles the First his Cromwell, and George the Third” before he was interrupted with cries of treason, and then completed the sentence stating “And George the Third may profit by their example!" Thomas Jefferson remembered that Henry seemed “to speak as Homer wrote” and that during the “most bloody debate” Henry spoke “torrents of sublime eloquence.”

After a spirited debate, the House of Burgesses passed the five resolutions. Henry and some of the other burgesses left town to return home. The next day, the remaining burgesses rescinded the radical fifth resolution. But newspapers throughout the colonies printed all five resolutions, along with two others that Henry may not have even introduced. The sixth and seventh resolutions asserted that inhabitants of the colony were not bound to pay taxes imposed by anyone other than their own assembly and that those who assert that another person had this right or authority would be considered an enemy. The public perception was that the House of Burgesses had adopted a more radical position than it did. The Virginia resolutions were an alarm that encouraged additional protest and resistance throughout the colonies.